The first time I contemplate death, I am 12 years old.

I have spent all year studying for a very important set of exams. My parents have told me repeatedly, that doing well in these exams will change my life for the better, give me a ticket out. That it will ultimately present me with opportunities to rise above my circumstances.

I study like never before. A part of me enjoys the monotony of my days. Even at that age, I begin to understand that I like to know things, that I thrive in structure and regiment, that I like to set goals and then bulldoze my way towards them.

My days, fairly simple, follow a strict pattern.

I wake up and go to school. When I return home, my father heads to the hawker stall next to our block of flats to pick up lunch. He orders some version of the same thing which I love – rice, with mutton curry, a piece of fried chicken, an egg omelette and two vegetables, usually some form of gourd and cabbage. Then, we sit at our dining table and share this meal, him picking apart the chicken from the bones, me enjoying the reprieve from staring at my notes and books. Some days, he buys me a little treat, a cake roll that we amicably share for dessert.

Then, the afternoon session of studying begins. My father grills me on my notes, gives me timed assessments while I work through pages and pages of mock exam papers. It sounds like grind, and it probably was, too much grind for a child of that age, but I remember the sweet satisfaction of getting things right, of knowing, of feeling on top of things.

I sit for my exams, and while I now cannot remember how I felt after I completed them, I recall telling my parents that maths is tough, because well, maths is always tough.

Then, without any warning, as I wait for my results, my thoughts turn towards dying.

They are not specifically about ending my life, per so, though I casually contemplate an end of some sorts. My thoughts circle around the same questions – what will happen to me if I failed? How will I face my parents? What kind of future will I be doomed for?

So, I contemplate death as an answer to this possible problem, even going as far as to write a suicide note to my parents. In the note, I write that I am sorry for disappointing them, that I had really tried my best, my very best, and that I did not mean to be such an abject disappointment, a failure. As I write this note, I cry. I contemplate getting ready to end it all, though I do not have any idea about what that means, only that it seems like the right thing to do if things are to go awry.

Of course, in the end, nothing untoward happens. I do well enough in the exams and go on to make my parents proud. Many years later, I discover my “suicide letter” in an old diary and read through it. This time, I cry again, mostly from devastation at the thought of my 12-year old self’s anxiety, worry and fear. I wonder how much pain this child must have carried in her to think that ending her life would seem like a solution for anything at all.

I still have this letter, kept as a reminder. That sometimes, the dying begins at a very young age and has very little to do with any kind of ending. Sometimes, it is the slow-burn destruction of a child’s confidence and psyche that she carries like cancer in her skin until one day, it finally decides to explode.

+++

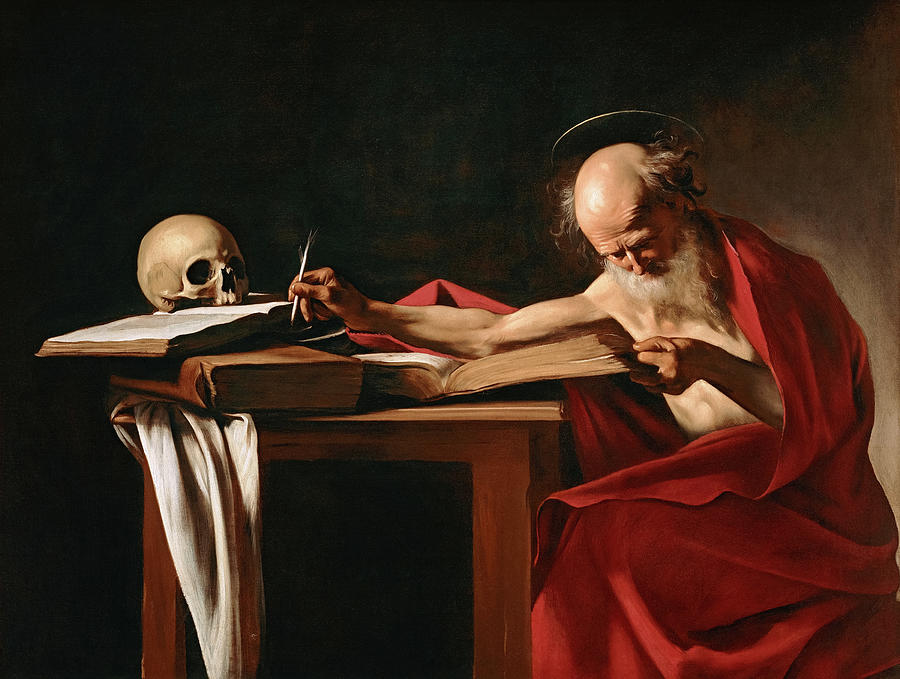

The second time death and I cross paths, I am 25 years old and participating in a death meditation.

My parents are attending a three-week spiritual retreat in Varanasi while I am travelling in China with my best friend and his partner, on a seeking sojourn of my own.

Two weeks later, as I return to Singapore, I receive a call from my father. My skin prickles, this is the first time I hear from him, and something tells me that whatever he will share is not going to be pleasant. His voice calm, he says that my mother has fallen deathly ill, and that it may best for me to head to India immediately if I wanted to see her alive.

I arrive in Varanasi the next day, my heart in my throat. I see my mother in poor shape, though the doctors tell me that the tide has miraculously turned for the better. I stay in Varanasi for three more weeks, taking turns with my father to nurse my mother. When I have some free time, to distract myself, I attend the programme that my parents had registered for.

This is how I end up in an auditorium filled with dinky mattresses. I lie on my back, eyes closed, and begin to take deep breaths as a man with a deep baritone takes me through the meditation. I am asked to think about my earliest memories. As my body continues to sink into the mattress I am lying in, different memories begin to flash through my mind, memories that I thought had been long-buried.

A teenager me, hurling sharp, poisonous barbs at my mother in the middle of an argument. A pre-teen me, serious and so cocksure (and precisely because of that, so terrified) of life. A smaller me, struggling to leave my parents, afraid of going to school. A baby me, crawling on the floor, my grandmother and mother watching over me.

And then, something strange, rising from the subconscious. The picture of my mother, much younger, rubbing her swollen belly, crying. An abject, alien sadness rising from within, the taste so overwhelming that I begin coughing and choking.

I wake with a gasp, almost as if I am resurfacing from the oceanic depths of my memory, as if I am coming back to life, this life. This time, I do not need to contemplate death. I think I have brushed it, just so, with my fingertips, in that little space before death ends and life begins.

+++

The next time death and I meet, we begin a soft, flirtatious dance with each other, our bodies intimately meeting, twirling.

I have recently been diagnosed with cancer. Mortality is at the front and centre of my thoughts. I am 32 years old, and it feels impossible to think about any kind of future because there is a strange blanket fear of what if I do not make it into the future. My oncologist asks me if I have cancer, and I say no, that the cancer has been removed from my body the day I had my surgery. I am cancer-free, I declare.

And yet. And yet. The metallic taste of fear lingers at the back of my throat.

Chemotherapy takes a toll on my body. The heaviness of my limbs, the loss of hair. I find myself lying on my back, on the cold marble floor of my home, tears leaking out of my eyes. There is a strange moaning sound coming from me, from a place where the grief is so vast – the grief of a possible future lost, the grief of a past I do not think I fully appreciated. As the pain starts to creep up my back, as my bones feel heavier and heavier, I think to myself, surely, now, surely this time, I will die.

Surely, it is better to be dead than to be alive like this.

My question remains unanswered, left adrift in the vastness of this ether, my broken existence.

Somehow, I make it through four chemotherapy cycles.

When I am officially done with my immediate cancer treatment a few months later, my face is wan and pale. My eyes are dull. I have no hair almost everywhere – my eyebrows are hanging on for dear life. My body still feels leaden, a deadweight.

That’s when I start again, a seeking sojourn of a different kind. I want to feel a lightness of being again. I want to throw off this heavy cloak of worry and uncertainty and fear. I want to tell death, wait. Now is not the time for you and me to meet. We are still dancing, but now, our bodies are no longer touching. Death’s seductive smell feels like a construct of my imagination.

Yet, when I take a deep breath, my chest feels hollow, damp.

I end up in the hallways of the wellness retreat, I start craniosacral therapy. During my second session, my therapist lifts my right leg, and it feels like a cavity in my heart rips opens. I let out a guttural cry, and weep and weep. I know not the reason for my sadness, or perhaps, I know it all too well. It does not matter. The only thing that matters is that the emotion needs to find its way out, and it does.

That day, for the first time, I feel something start to lessen.

Soon after, I go for my first sensory deprivation float.

I have entertained reservations about float therapy for a long time, primarily because I am the least comfortable in water. The thought of having my senses blanketed while I float, suspended, of drifting in the ether of existence.

The familiar metallic taste of fear returns as I contemplate this.

Yet, something tells me that I am on the precipice of a new discovery. That perhaps, with this complete shutdown of my senses, I will have the courage to really go inwards, to fully reckon with all the brokenness and the darkness, to see my shadow selves in the eye and say, I see you, I love you.

So, with my heart in my mouth, I acquiesce and allow myself to surrender to the experience.

There is a meditation song that plays loudly through the room. I have ear plugs in, the gong sounds and it reverberates through me. I take a deep breath; the cover of the float comes down gently with a whizz. Then, I reach out to the button beside me and press it.

Instantly, I am plunged in darkness. My eyes see nothing. The music fades away and I hear nothing. My body is suspended in salt, so much salt. The salt in me surges up to meet the salt I am floating in. I cannot tell if my eyes are open or closed – the darkness is absolute. My heart is thundering in my ears, and I force myself to breathe slowly, deliberately.

I don’t know if I succeed, but what I do know is this.

I leave my body. There is a moment where I feel the darkness seeping into my skin, my forehead, right into that space in between my eyebrows. I feel an untethering, a loosening. I think I am disintegrating into the darkness but I do not know for sure, I cannot tell. I have never been here before.

I do not know how much time passes, only that I have left. I am going somewhere. Or maybe I am finally arriving. Suddenly, my hand reaches out, I see it, the outline of my fingers, the same fingers that were passed down to me from my grandmother. My hand reaches out and grabs a door handle that has also just materialised. I turn the handle, feel the tactile motion of it. I hear the door swing open and before I can see what lies within, I physically slam back into my body.

My body jerks, my eyes snap open and my heart pounds.

Almost immediately after, the meditative music resumes, calling me back into the world of living. Minutes later, when I rise out of the pod, and catch sight of my face in the mirror, I stop.

My eyes are glowing.

+++

I go back to this often, the door, the blackness, the act of turning a handle.

I think of what I felt before starting this journey – that I was on the edge of the precipice of something new. I think of how I have reckoned with my shadow selves, over and over. I wonder and wonder – what would I have seen behind that door, who would I have met.

I think about touching that liminal space between death and life, how it showed me a glimpse of the things we carry when we travel from one life to the next. I wonder if it would have been different if I didn’t carry my mother’s sadness in my bones, if I hadn’t inherited the melancholy of my ancestors in my mother’s womb.

I think about the little girl who began cajoling death when she didn’t know what it meant. I think about the ways in which she wove the pain and pressures into her little spindly limbs, and whether she knew how she would spend the rest of her life reckoning with it.

I wonder if death would have still come calling with cancer if I had done anything differently.

My wondering leads me nowhere.

Yet, I contemplate death less. Death feels like a faraway memory, one that I pull out to furnish my words like the one I am writing to you today. The metallic taste of fear is less potent, as if soothed by the ways in which I have turned up for my body and my mind in the last few months. As death recedes, life begins to cautiously enter these spaces.

A flower here, a hope there. A plan for the future here, a giggle there. A piece of cake here, grass under my toes there.

And so, slowly, slowly, I begin to walk in the light again.

I tell my friend death, not today, sir. There will come a time. But today is not the day.

I move forward.

…

Over the years, Arathi Devandran has written for e-zines and publications on a range of issues, serving as a youth columnist, general observer of the human condition, and dissector of the specific experiences of being a South Asian woman in a patriarchal and parochial world. More recently, she has become interested in exploring themes of inter-generational familial relations and navigating the complexities of self-growth through personal essays and autofiction. Arathi is currently working on her full-length manuscript. Her work can be found here.

A variation of this piece was commissioned by Soma Haus (Singapore) for Breast Cancer Awareness Month.

Leave a comment